Welcome back to

evolution of venom, Today’s blog topic, we will be covering bees, wasps,

centipedes and moths and how they use their venom. A brief recap: we covered

cone snails, jellyfish, and sea urchins and how they use their venom.

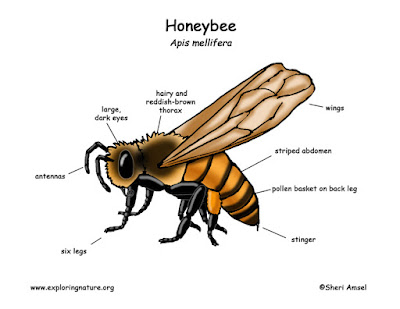

Bees are flying insects that belong to the order Hymenoptera, superfamily Apoidea that produces honey and beeswax, they are known for their role in pollination and live mostly in large colonies (Danforth et al, 2006). Bee venom comes from the poison gland that contains a variety of toxins and chemicals, bee stings are dangerous to both humans and bees as the stinger that introduces the venom into the human’s system is torn from the abdomen causing the death of the bee. Some humans can have a severe reaction to bee venom causing shock and death (Warrell, 2015). Below is a diagram of a honey bee.

Diagram of honeybee by exploringnature

By WikipedianProlific at the English language

Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Centipedes are

arthropods belonging to the class Chilopoda,

Phylum Arthropoda. Their body is made

up of a flattened head with a trunk composed of segments (somites). The head

has long antennas, jaws and two pairs of maxillae used for food handling. The

appendages on the trunks first segment has claws that have been modified to

allow poison glands to deliver venom to stun or kill prey (Centipedes, 2017). Below

is a diagram of a centipede.

Diagram of a centipede by enchantedlearning.

By Centro de Informações Toxicológicas de Santa

Catarina

In next weeks’

blog, we be covering vertebrates that use venom. Below are the articles used in

this week’s blog for more reading about these animals.

References

Centipede. (2017).

In P. Lagasse, & Columbia University, The Columbia encyclopedia (7th ed.).

New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Danforth, B.N.,

Sipes, S., Fang, J. & Brady, S.G. 2006, "The History of Early Bee

Diversification Based on Five Genes Plus Morphology", Proceedings of the

National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 103, no. 41,

pp. 15118-15123.

Spadacci-Morena,

D.D., Soares, M.A.M., Moraes, R.H.P., Sano-Martins, I.S. & Sciani, J.M.

2016, "The urticating apparatus in the caterpillar of Lonomia obliqua

(Lepidoptera: Saturniidae)", Toxicon : official journal of the

International Society on Toxinology, vol. 119, pp. 218-224.

Warrell, D.A.

2015;2016;, "Venomous animals", Medicine, vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 120-124

Wasp. (2017). In P.

Lagasse & Columbia University, The Columbia encyclopedia. (7th ed.).

Picture references